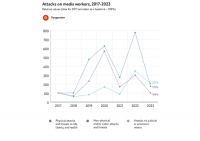

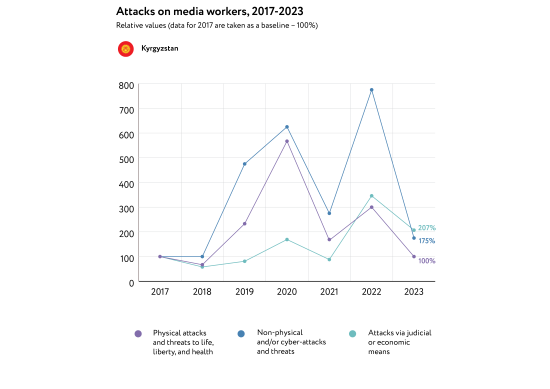

Attacks via judicial means has remained the main method of exerting pressure on professional and civilian media workers, and editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets, experts said.

This media risk has been identified for the last years.

The monitoring group of the School of Peacemaking summed up the preliminary analysis’ results of incidents against journalists and bloggers.

In 2023, more than 50 attacks on freedom of speech/expression were recorded in Kyrgyzstan. Most of these incidents were done using judicial methods: the interrogations, arrests, pre-trial detentions, threats, blocking e.t.c.

The researchers also note that decreased perceptions of freedom of expression in the local context had an impact on incidents against media workers.

This is due to various restrictions, including freedom of peaceful assembly, strict legislative initiatives against NGOs, the initiation of a new restrictive law "On the Media,” and the growth of censorship and self-censorship.

The School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in partnership with the Justice for Journalists, has been constantly monitoring and analyzing incidents that are published on the Media Risk Map since 2017.

The full report, "Attacks on media workers in Kyrgyzstan,” will be available in 2024.

The School of Peacekeeping and Media Technologies in Central Asia, together with leaders from Justice for Journalists, has been constantly monitoring and analyzing incidents that are published on the media risk map since 2017.

The full report, "Attacks on Kyrgyz media workers,” will be available in 2024.

Previous year's report here

Canva illustrative image.

The year 2023 in Kyrgyzstan was marked not only by increased political censorship but also by a crackdown on the media and civil society amid the parliamentary review of two bills: the law "on NGOs” (similar to the Russian "foreign agents” legislation) and law "on mass media”. On 22 February 2024, the law "On NPOs” was adopted after a second reading. The law "on mass media” provides for a number of excessive restrictions, including state regulation of the media and online platforms and sanctions for "abuses of freedom of speech.” As a result, the persecution and harassment of independent media workers who are critical of the government has notably intensified. In addition, an unconstitutional ban on peaceful assembly was introduced.

The year 2023 in Kyrgyzstan was marked not only by increased political censorship but also by a crackdown on the media and civil society amid the parliamentary review of two bills: the law "on NGOs” (similar to the Russian "foreign agents” legislation) and law "on mass media”. On 22 February 2024, the law "On NPOs” was adopted after a second reading. The law "on mass media” provides for a number of excessive restrictions, including state regulation of the media and online platforms and sanctions for "abuses of freedom of speech.” As a result, the persecution and harassment of independent media workers who are critical of the government has notably intensified. In addition, an unconstitutional ban on peaceful assembly was introduced.