Experts recommend promoting self-regulation in online communities, enhancing media literacy, developing tolerant speech strategies as effective tools to overcome hate speech and discrimination on the Internet.

On May 12-13, the 7thCentral Asian Forum "Development of Internet Sphere in Central Asia InternetCA-2016” was held in Almaty (Kazakhstan) on the subject "Calls to Counter Destructive Content on the Internet: Xenophobia, Propaganda, Language of Intolerance”.

The main topics of the discussion referred to media wars, media manipulations, hate speech, propaganda, differences between the freedom of expression and intolerance, understanding of this ways, in order to avoid the total control of the internet and pressure on freedoms. International and regional specialists’ demonstrated best cases, recommendations and held master classes.

Journalism must become the key vehicle in countering hate speech, xenophobia and propaganda in media and on the Internet.

On the occasion of the World Press Freedom Day celebrated on May 3, 2016, the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Central Asia encourages the promotion of quality journalism and ethic communications in order to counter modern challenges.

In Central Asia, as well as in many other countries around the world, the crisis in the media sphere has been caused by the governmental control, lack of journalism standards, and increasing language of intolerance. Continuous monitoring and studies of media and Internet highlight such trends. Xenophobia and its various types are expressed in open or veiled forms of intolerance in the media environment, which results in the hostility in response, negative impact on the audience, and encouragement of inhumane stereotypes in the society. The negative discourse is promoted by the propaganda, network aggression, and a series of fibs circulated in media and Internet.

ASTANA, 19 April 2016 – An OSCE-supported two-day training seminar on

protecting freedom of expression and countering hate speech on the

Internet began today in Astana.

ASTANA, 19 April 2016 – An OSCE-supported two-day training seminar on

protecting freedom of expression and countering hate speech on the

Internet began today in Astana.

Some 40 journalists, lawyers, academics, representatives of the Justice, Interior, Investment and Development Ministries, the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Anti-terrorism Centre under the National Security Committee and Supreme Court gathered to discuss the relationship between media and hate speech policies and ways to enhance co-operation between governments, civil society and media organizations.

The event was co-organized by the OSCE Programme Office in Astana and the Legal Media Centre, a non-governmental organization based in Kazakhstan.

The public discussion "Hate Speech and Discrimination through the Media. Trends, Influence, Challenges, Countering” was held on February 10, 2016.

The participants of the event were Shawn Steil, Canada’s Ambassador to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Sanzharbek Tazhimatov, expert of the department of ethnic, religious policies and interaction with civil society of the Presidential Administration of the Kyrgyz Republic, Ablabek Asankanov, head of Monitoring Center of GAMSUMO [State Agency for Local Government Affairs and Ethnic Relations] of the Kyrgyz Republic, representatives of international, civil, religious organizations, and media experts.

Interactive lecture "Freedom of expression: how not to suffer for statements in media and on the Internet and not to violate the anti-extremism law. Kyrgyz reality and Russian practices” with participation of invited expert Alexander Verkhovsky, director of Sova Center for Information and Analysis (Russia) was held on February 4, 2016.

Experts, lawyers, journalists, representatives of international and public organizations were invited to the event.

School of Peacemaking and Media Technologies has presented its interim report "Hate Speech in

Media, Internet and Public Discourse of Kyrgyzstan – 2015”.

School of Peacemaking and Media Technologies has presented its interim report "Hate Speech in

Media, Internet and Public Discourse of Kyrgyzstan – 2015”.

The report was based on the analysis of hate content carried in the surveyed print, broadcast, online media and social networks in Kyrgyz and Russian languages for November-December 2015 and data compared to other periods of the year, as well as the findings based on field studies.

The freedom of expression in the media scene of Kyrgyzstan is closely related to the lexis of hate, which is based on clearly xenophobic statements, political incorrectness and emphasizes poor journalistic standards in the media, while posts in social networks sometimes provoke network aggression. Despite the fact that Kyrgyzstan ranks higher in the Press Freedom Index[1], than the neighboring states in Central Asia, it still has problems with ethics.

The discriminatory language against minorities was also detected in those media outlets that describe themselves as analytical media. In their articles and reports about the problems faced by minorities, authors also create their negative image. Thus, the media contribute to the spreading of xenophobia – ethnic, religious, social and other types.

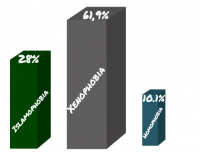

In 2015, the number of social groups that are seen as victims of hate speech and possible victims of hatred-based crimes has increased. If in previous years experts mainly identified definite ethnic groups, the analysis of the media sphere by the end of the year showed that the main target of hate speech in Kyrgyzstan are ethnic groups, Muslims and LGBT.

The Representative Office of

the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) in Kyrgyzstan, with the

participation of representatives of the CIS Antiterrorist Center, Ministry of

Internal Affairs, the State Commission on Religious Affairs, NGOs, experts and

researchers, discussed the main causes of radicalization and the ways to

prevent them.

The Representative Office of

the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) in Kyrgyzstan, with the

participation of representatives of the CIS Antiterrorist Center, Ministry of

Internal Affairs, the State Commission on Religious Affairs, NGOs, experts and

researchers, discussed the main causes of radicalization and the ways to

prevent them.

Such data were

submitted in the report of School of Peacemaking and Media Technologies that

was presented on November 19 at the forum "Right to Equality and

Nondiscrimination: Peacebuilding and Prevention of Ethnic Conflicts”.

Such data were

submitted in the report of School of Peacemaking and Media Technologies that

was presented on November 19 at the forum "Right to Equality and

Nondiscrimination: Peacebuilding and Prevention of Ethnic Conflicts”.

The presentation was prepared under the media monitoring project supported by the Canadian Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI).

The report contained the trends and dynamics of ethnic stereotypes used, as well as the types of hate speech spread in the media and on the internet of Kyrgyzstan, spoken out by high profile speakers.

The School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Central Asia announces an annual competition among students from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan,…

25 journalists and media workers from various regions of Kyrgyzstan have been trained to counter the propaganda of violent extremism and hate in…